WZ: Well, y’know, I feel that it returns to the subject of the monkey, the ever-recurrent theme of the monkey, the mandrill, the gorilla. PM: ‘Porcelain Monkey’ from Life’ll Kill Ya returns to the subject of Elvis’s decline, which you also sang about in ‘Jesus Mentioned’… WZ: (Cracks up laughing) My girlfriend is in the next room – I don’t know how… I hope not! PM: Going by your songs, one might reasonably suppose you’ve had some trouble sustaining relationships. But I think that generally the terms we’re given are pretty hard to sort out, they’re a little baffling.

Course, there’s those around me who might disagree, but I think it’s been pretty easy. WZ: Mine? I think that life’s tough, I think mine’s been pretty easy. PM: Do you think your life’s been a tough one? My father was a Russian immigrant and he had precisely the same sense of humour. In May of that year, the present writer called Zevon at room 227 in the Sanderson Hotel in London the following is an edited transcript of the conversation. Strange thing was, he’d already recorded a swansong of sorts with Life’ll Kill Ya in 2000, a morbid, moving and of course funny essay on mortality that eerily predicted his body’s decay in songs like ‘My Shit’s Fucked Up’ and the title tune. His last words to his public remain posted on his website: “Enjoy every sandwich”. Zevon was diagnosed with an inoperable form of lung cancer in August of last year his response was to forego chemotherapy and concentrate on recording his last will and testament, The Wind. Thereafter, Transverse City (a cyberpunk dystopian concept album written after a Thomas Pynchon binge) and Mr Bad Example were patchy enough, but he was back on form in the late ’90s with Mutineer, Life’ll Kill Ya and My Ride’s Here, the latter featuring guests such as David Letterman and poet Paul Muldoon, that were among the best of his career. Most of all he survived himself, making the mother of all rehab albums in the form of Sentimental Hygiene in 1987, backed by REM. But nevertheless, he survived the booze, the broken marriages, the loaded guns and the interventions. Like Tom Waits, those early LPs sounded like quintessential west coast singer/songwriter recordings, but the core content was altogether more Chandler-esque: the barfly soap opera of ‘The French Inhaler’ the strung out junkie writer in ‘Carmelita’ the sex ’n’ drink ’n’ death vignettes of ‘Roland The Headless Thompson Gunner’, ‘Werewolves Of London’, ‘Excitable Boy’, ‘Lawyers Guns & Money’ and ‘Play It All Night Long’ (containing the classic Warren line, “There ain’t much to country livin’/Sweat, piss, jizz and blood”).Īnd of course, there were unbearably vulnerable alcoholic ballads such as ‘Desperados Under The Eaves’ and ‘Accidentally Like A Martyr’ that were Zevon’s speciality.

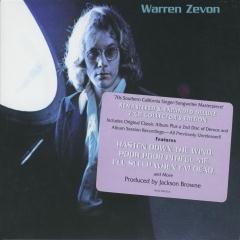

The son of a Russian fighter and gambler, and a piano prodigy who as a child knew Stravinsky, his first couple of albums contained expertly observed portraits of the beautiful and the damned among the ’70s LA coke and champagne set. Scott FitzZevon could scarcely have been more apposite. The singer was as comfortable with writers like Carl Hiaasen, Hunter S Thompson, Jonathan Kellerman and Thomas MacGuane as fellow musicians (although he had no shortage of distinguished fans and collaborators, including Bob Dylan and Neil Young). Jackson Browne dubbed him “the first and foremost proponent of song noir.” Bruce Springsteen called him “The good, the bad and the ugly… a moralist in cynic’s clothing”. Zevon coined so many brilliant lines that when his peers came up with quotes about him they tended to speak above even their own abilities. When Warren Zevon passed away on Sunday September 7, rock ‘n’ roll lost one of its great ironists and men of letters. In the article below – originally published in Hot Press in 2003 – Peter Murphy reflects on Warren Zevon’s legacy, and shares a transcript of a phone interview with the singer-songwriter from 2000:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)